Handling Memory Leaks in Rust

Rust’s low-level nature gives you access to resources and memory, so many developers choose Rust for their projects across various tech sectors. Ownership and borrowing are among the first concepts you’ll learn when dealing with Rust, as they form the primitives for how Rust handles memory.

Once in a while, you may experience memory leaks in your Rust projects due to many factors, from unsafe code to shared references, etc. Ideally, you’ll want to fix these memory leaks and ensure your programs are efficient, which may lead to performance gains and resource safety.

Memory Leaks and Unsafe Behaviour

Rust’s built-in ownership model and compile-time checks reduce the possibility and risks you’ll encounter with memory leaks, but they’re still quite possible.

Memory leaks don’t violate the ownership rules, so the borrow checker lets them slide at compile time. Leaking memory is inefficient and generally not a great idea, especially if you have resource constraints.

On the other hand, unsafe behaviour can also slide if you embed it in an unsafe block. In this case, memory safety is your responsibility regardless of the operation, e.g. (pointer dereferencing, manual memory allocation, or concurrency issues).

Memory Leaks via Ownership and Borrowing

Rust does not use a garbage collector. Instead, It uses ownership and borrowing (the borrow checker enforces the ownership model), which form the core principles for memory handling in Rust programs.

The borrow checker prevents dangling references, use-after-free errors, and data races at compile time before the compiler executes the program. Still, memory leaks can occur when memory is allocated without dropping it throughout the execution time. It’s safe to say it’s safe; sometimes, there may be no issues.

Here’s an example of how I implement a doubly linked list. The program would run successfully, but there would be a memory leak issue.

use std::rc::Rc;

use std::cell::RefCell;

struct Node {

value: i32,

next: Option<Rc<RefCell<Node>>>,

prev: Option<Rc<RefCell<Node>>>,

}

fn main() {

let first = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Node {

value: 1,

next: None,

prev: None,

}));

let second = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Node {

value: 2,

next: Some(Rc::clone(&first)),

prev: Some(Rc::clone(&first)),

}));

first.borrow_mut().next = Some(Rc::clone(&second));

first.borrow_mut().prev = Some(Rc::clone(&second));

println!("Reference count of first: {}", Rc::strong_count(&first));

println!("Reference count of second: {}", Rc::strong_count(&second));

}

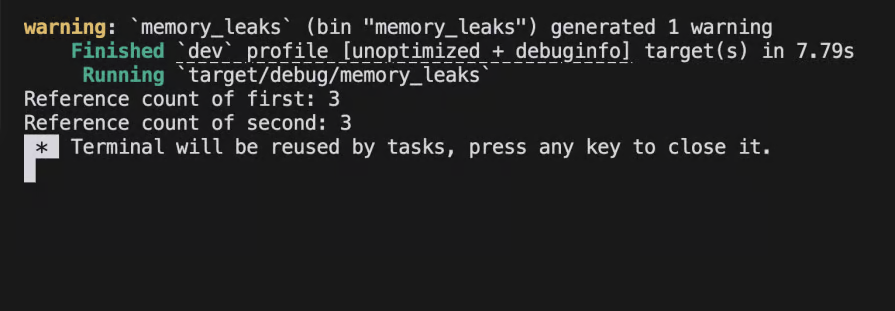

The problem with this program occurs with the circular reference between two nodes, resulting in a memory leak. Since RC smart pointers don’t handle cyclic references by default, each node holds a strong reference to the other, creating a cycle.

After the main function is executed, the reference count for the second and first variables will equal the first value, although it’s no longer accessible. This results in a memory leak since none of the nodes are deallocated.

You can fix cases like this by:

- Using weak references (Weak

) for one link direction. - Manually breaking the cycle before the end of the function.

Here’s an example where I address the reference problem with Weak pointers on the prev field.

use std::rc::{Rc, Weak};

use std::cell::RefCell;

struct Node {

value: i32,

next: Option<Rc<RefCell<Node>>>,

prev: Option<Weak<RefCell<Node>>>,

}

fn main() {

let first = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Node {

value: 1,

next: None,

prev: None,

}));

let second = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Node {

value: 2,

next: Some(Rc::clone(&first)),

prev: Some(Rc::downgrade(&first)),

}));

first.borrow_mut().next = Some(Rc::clone(&second));

first.borrow_mut().prev = Some(Rc::downgrade(&second));

println!("Reference count of first: {}", Rc::strong_count(&first));

println!("Reference count of second: {}", Rc::strong_count(&second));

println!("First value: {}", first.borrow().value);

println!("Second value: {}", second.borrow().value);

let next_of_first = first.borrow().next.as_ref().map(|r| r.borrow().value);

println!("Next of first: {}", next_of_first.unwrap());

let prev_of_second = second.borrow().prev.as_ref().unwrap().upgrade().unwrap();

println!("Prev of second: {}", prev_of_second.borrow().value);

}

You can use <Weak<RefCell<Node>>> to prevent the memory leak since the Weak reference doesn’t increase the strong reference count, and the nodes can be deallocated.

The std::mem::forget Function

You can intentionally use the std::mem::forget function to leak memory in your Rust project when necessary. Rust includes the function for this behaviour, so the compiler considers it safe.

Even if the memory isn’t reclaimed, there’ll be no unsafe access or memory issues.

The std::mem::forget takes ownership of a value and forgets it without running the destructor, and since resources held by aren’t released, there would be a memory leak.

use std::mem;

fn main() {

let data = Box::new(42);

mem::forget(data);

}

At runtime, Rust skips the usual cleanup process, the data variable’s value is not dropped, and the memory allocated for data is leaked after the function is executed.

Leaking Memory With Unsafe Blocks

Using raw pointers gives you the responsibility to manage memory. Here’s how using raw pointers in an unsafe block may lead to a memory leak.

fn main() {

let x = Box::new(42);

let raw = Box::into_raw(x);

unsafe {

println!("Memory is now leaked: {}", *raw);

}

}

In this case, the memory isn’t freed explicitly, and there’d be a memory leak at runtime. After the program’s execution, the memory will be deallocated, so this isn’t the most critical case, but it’s not memory efficient.

Deliberately Leaking Memory with Box::leak

The Box::leak function allows you to leak memory deliberately. This function is proper when you need to use a value throughout runtime.

fn main() {

let x = Box::new(String::from("Hello, world!"));

let leaked_str: &'static str = Box::leak(x);

println!("Leaked string: {}", leaked_str);

}

Don’t abuse this; leak is helpful if you need a 'static reference to meet specific API requirements.

Fixing Memory Leaks in Rust

The golden rule for fixing memory leaks is avoiding them in the first place, except if your use case requires you to. Following the ownership rules is always a great idea. In fact, with the borrow checker, Rust is enforcing great memory management practices, and that’s great.

- Use references when you need to borrow values without transferring the ownership.

- You can try out Miri to detect undefined behaviour and catch memory-leak-related bugs.

- Implement the

Droptrait on custom types for cleanups. - Don’t use

std::mem::forgetunnecessarily. CheckoutBox<T>for automatic cleanups on heap allocations when a value is off the scope. - Don’t throw

unsafeblocks everywhere without reason. - Use

Rc<T>orArc<T>for shared ownership of variables. - Cautiously

RefCell<T>orMutex<T>for interior mutability. They’re helpful if you need to ensure safe concurrent access.

Following these tips, exploring building more Rust programs on a lower level in terms of memory should be everything you need to handle memory leaks in your Rust programs.

Conclusion

You’ve learned how memory leaks can happen in your Rust programs and how you can simulate them in necessary cases for different purposes, like having a persistent variable in a memory location at runtime.

Understanding the fundamentals of ownership, borrowing, and unsafe Rust would help manage memory and reduce memory leaks.